Tetanus immunity treats pancreatic cancer in mice

Pancreatic cancer has one of the lowest survival rates of any form of the disease. Most people survive less than a year after diagnosis because it is often noticed late, when the cancer has spread to other parts of the body. Once the cancer has spread, the main treatment is chemotherapy, which can only slow its growth.

New cancer therapies that activate the immune system have led to significant improvements in patient care. In melanoma, for example, immune therapies have led to long-term remission in cases that were previously incurable. Also called checkpoint inhibitors, these drugs counteract the immune-suppressing activity of cancer in the hope that the immune cells will recognize and attack the tumor. However, this type of approach has not had much success in pancreatic cancer.

“The problem is that pancreatic tumors are not ‘foreign’ enough to attract the attention of the immune system and can usually suppress any immune responses that occur,” said Claudia Gravekamp, PhD, associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. in New York, in a statement.

Toxoid Priming

Researchers led by Gravekamp have tested a new approach that uses childhood tetanus vaccines to boost the immune system against cancer cells.

Most children worldwide are given tetanus vaccines that contain a ‘toxoid’, which is similar to the toxic protein produced by the bacteria that cause tetanus. The toxoid is harmless, but it stimulates the immune cells to attack when exposed to it again in the future, even many years later.

The team hoped this priming would be enough to activate the immune system to fight tumors. To test this, they studied lab mice that were genetically engineered to develop pancreatic cancer by vaccinating them against tetanus during childhood.

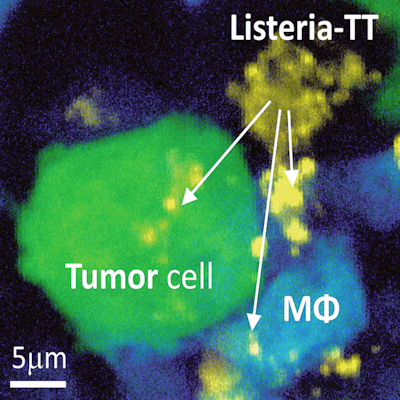

Once the cancers had developed, the researchers injected the mice with modified Listeria bacteria that produce the toxoid. Although Listeria, a leading cause of food poisoning, is usually best avoided, the form used was weakened and caused no side effects. Even though the bacteria did not directly target the tumor, the cancer’s own defenses make it vulnerable to this approach (Sci Transl Med, March 23, 2022, Vol. 14:637, eabc1600).

“Our treatment strategy basically takes advantage of the fact that pancreatic tumors are so good at suppressing the immune system to protect themselves. This means that only those Listeria bacteria in the tumor area survive long enough to infect pancreatic tumor cells and healthy cells don’t.” do’ not get infected,” says Gravekamp.

Combining treatments

When the toxoid-carrying Listeria was combined with gemcitabine, a chemotherapy drug that reduces immune suppression, the tumor shrank by more than 80%, including those that had spread to other organs. The mice also survived two months longer than those left untreated — a 40% increase.

“The findings indicate that this treatment approach could be a useful immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer and other cancers, such as ovarian cancer, that remain difficult to treat,” Gravekamp said.

To ensure that the Listeria could reach the tumors directly, the researchers injected them into the abdomen of the mice. Although intravenous injection is more common in the clinic, it would result in the bacteria being cleared into the blood by the immune system before they reach the tumors. The team is now investigating whether this procedure can be performed safely in humans before testing the treatment in clinical trials.

The strategy of using bacteria to treat cancer is growing in popularity. Recently, researchers have also developed a new technique that allows bacteria to evade the immune system so that they can deliver toxins to tumors.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net

Comments are closed.